I should know by now that the holiday season is exhausting for singers, especially those who sing for Christmas at church. I thought I’d be done with this post and another earlier this month, but obviously that didn’t happen. Alas.

Originally, I promised a post that would dive into a detailed explanation regarding how I, a seasoned multitracker since before the popularity of that app Acappella, created my Maddalena madrigal recording. But, I’ve since realized that such a detailed, chronological explanation would require an even longer and more insufferable post than the last. So instead, I’m going to provide something a little briefer and simpler: some tips and tricks I’ve used to multitrack in a relatively cost-effective way. So with that out of the way, let’s get started.

#1: Make a Click Track

A click track is exactly what it sounds like: a track full of “clicks” to help you keep time as you record. It’s basically like singing to a metronome, and it helps you line up all your tracks in post. Some might argue that singing to a click track doesn’t feel musical, and perhaps that’s true. Personally, I think it’s a small setback a little practice can fix.

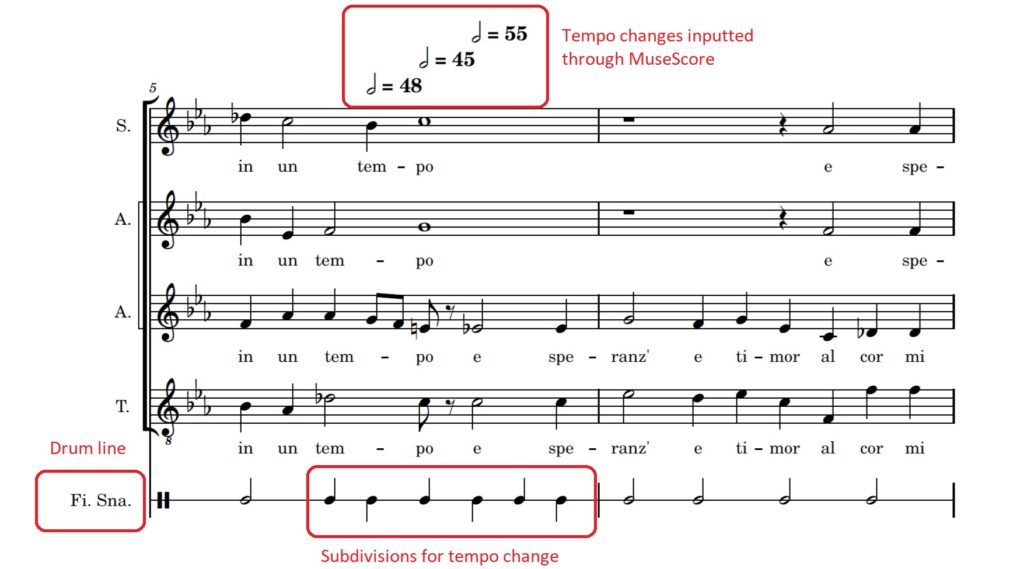

“But a metronome can’t make subtle tempo changes at phrases!” you say. Well, I’m happy to inform you that you can make variable click tracks, which go faster or slower according to your musical choices. Most Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) can make click tracks, though I personally prefer to save money and make click tracks through the free engraving software, Musescore. What I do is input the melody of the piece (all four voice parts in the Maddalena example below) into Musescore with a drum line. Then I use Musescore’s MIDI playback to listen to the melody and add tempo changes where I see fit. I subdivide—utilize smaller rhythmic values—when there’s a tempo change so I’ll be warned that it’s coming. Finally, I use Musescore to export the MIDI audio of the drumline alone and voila, my click track is born.

Admittedly, it’s a rather barbaric way to make click tracks, but it works and it doesn’t cost anything, so I have no complaints.

#2: Use the Right Headphones

In order to multitrack, you have to listen to one thing while simultaneously singing and recording another. If you’re listening to a click track, you don’t want those obnoxious clicks to bleed into your recordings. So, it’s crucial to use the right equipment so you can listen to your click track without it disrupting your recordings.

In order to multitrack, you have to listen to one thing while simultaneously singing and recording another. If you’re listening to a click track, you don’t want those obnoxious clicks to bleed into your recordings. So, it’s crucial to use the right equipment so you can listen to your click track without it disrupting your recordings.

First, use wired headphones. Wired earbuds can work in a pinch, but they can leak sound, so if you’re using a sensitive microphone, the sound might still bleed over. You also want to avoid using wireless gear, because Bluetooth delays can cause major issues when recording.

Second, make sure your headphones are closed back. Headphones can generally be separated into two types: open backed and closed back. Open backed headphones are designed so you can hear external sounds around you, while closed back headphones are designed to block out external sound. Because open backed headphones allow external sound in, though, they also can allow sound out, so you can encounter the same bleeding issue you do with earbuds.

Third, shoot for over-ear headphones. These are designed to cover your entire ear, which can be very annoying for long periods of time. But when the headphone covers your whole ear, it forms a seal that makes it more unlikely for your click track to seep through. So while it’s possible to make good recordings without over-ear headphones, they’re often a great help.

If you Google the best wired, closed back, over-ear headphones, you may see expensive brands like Beats show up. Unless you want to, don’t bother going for those; cheap headphones will do just fine. My headphones are from OneOdio, and I got them on sale for $20.

#3: Invest in the Right Gear

If you plan to multitrack consistently, you’ll want a good microphone to catch your sound. If you don’t record all that much, you might consider a USB microphone for higher convenience; Blue microphones, like the Blue Yeti, are especially solid. If you plan to record a lot, you might consider investing in an XLR microphone instead. XLR microphones will generally produce higher quality than USB ones, but they’re inherently more expensive, because they don’t plug straight into your computer. Instead, you have to buy the microphone, an XLR cable, and an audio interface, which will be able to plug into your computer. AudioTechnica makes great XLR microphones for relatively cheap prices, at least as far as microphones go… check out the AT2020 for a solid budget choice.

If you plan to multitrack consistently, you’ll want a good microphone to catch your sound. If you don’t record all that much, you might consider a USB microphone for higher convenience; Blue microphones, like the Blue Yeti, are especially solid. If you plan to record a lot, you might consider investing in an XLR microphone instead. XLR microphones will generally produce higher quality than USB ones, but they’re inherently more expensive, because they don’t plug straight into your computer. Instead, you have to buy the microphone, an XLR cable, and an audio interface, which will be able to plug into your computer. AudioTechnica makes great XLR microphones for relatively cheap prices, at least as far as microphones go… check out the AT2020 for a solid budget choice.

Once you have a microphone, you’ll also want to invest in a mic stand and a pop filter. Sometimes, you can get online microphone bundles that include these items, but if you don’t go for a bundle, you’ll have to buy them separately. Unless you want to record while sitting, you’ll want to invest in a tripod boom stand, which stands on the ground rather than a table as the Blue Yeti pictured above does. Meanwhile, pop filters prevent your sharper consonants (T’s and S’s especially) from sounding unnaturally loud in the mic. They also prevent you from accidentally spitting into the microphone, which will help preserve the electronics for longer.

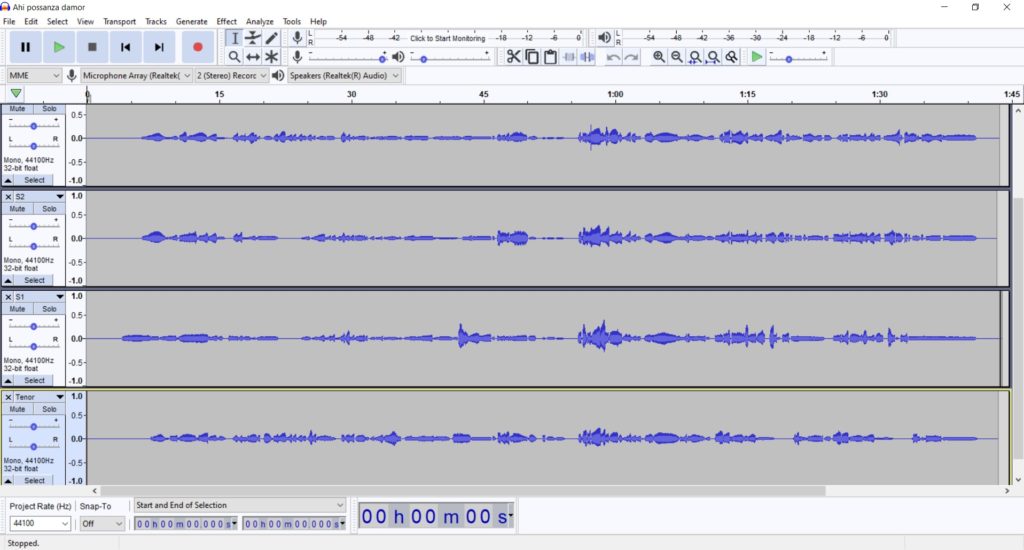

Once you have your gear, you’ll need a computer through which to record, but you’ll also need a DAW which will allow for recording, playback, and editing. If you have a Mac, congrats! Your computer comes with GarageBand, a free program that will allow you to do everything you need. If you are already subscribed to Adobe Creative Cloud, you might want to try Adobe Audition for a relatively little fee. I personally keep with my barbaric trends and use Audacity, a free, open-source program that works for PC and Mac. It looks old-fashioned and doesn’t have the fancy plugins of a costing DAW, but for multitracking, it’s completely serviceable.

#4: Record in a Dry Space

Most recording engineers will tell you that, unless you’re doing a live recording in a nice acoustic space, you’ll want to record in a dry space, or a space with little echo. In other words: don’t record in the bathroom, regardless of how great you sound in there.

It goes a little further than that, though. Sound reflects off hard surfaces, so even a simple square room with drywall and linoleum flooring will create echoes. The cure to this is to surround yourself with soft items. Try a room with carpets, tapestries, or curtains. You can spend money on specialized foam to put on your walls, but you can still get fairly decent results without that. My cheapskate workaround is to record at my closet of hanging clothes; I don’t fit in there myself, but at least I can sing at a microphone backed by soft things.

It might sound like a bother to go through, but it’s all to capture audio with the least amount of distortion. It will make your voice sound horrible compared to the bathroom, but once you do it, you’ll be able to add reverb and whatnot in your DAW during post-production. And it’s far easier to add reverb than it is to take it out.

#5: Punch In/Out as Needed

I and many other musicians have what I call “answering machine syndrome:” we hear recordings of ourselves and cringe. Every mistake feels blaringly obvious, even if the layperson listener doesn’t hear them at all. But that’s the beautiful thing about recording: you can fix mistakes.

Don’t try to re-record tracks from scratch, though. If you listen to your recording and hear an error at a specific phrase, just re-record that part. There are several terms for this, but I learned it as punching in and punching out.

To get into the flow of the phrase, you’ll want to re-record from slightly earlier than the place you’re aiming for and end your recording slightly later. For example, if I recorded “these are a few of my favorite things” and I wanted to fix the pitches on “favorite,” I’d probably re-record the whole phrase, but only paste in my updated version of the word. It helps the final recording feel more natural.

In general, I would recommend two full takes (uninterrupted recordings of everything) of any given piece before punching in and out as needed. But remember—only punch in and out as needed. Recording is deadly to perfectionists because it can be never-ending. Remember that, regardless of how much you punch in and out, no recording will be perfect, and that’s okay.

~~~

Multitracking is a constant learning process. There are always new techniques to try, new programs to try, and so on. But like with recording, there’s always a time to stop, and I think it’s time this post did the same. Hopefully this was an interesting and insightful read!

This Post Has One Comment

Really informative and wonderful complex body part of articles, now that’s user friendly (:.