I haven’t posted anything to my YouTube channel in well over a year, yet here I am, returning online with the multi-track, split-screen fad that was far more popular last year than it is now. Although the final product isn’t nearly polished enough for my perfectionist tendencies, I put a lot of thought into it, and I’d like to be an absolute nerd and share those thoughts here.

This is going to be separated into two parts: a veeeery long post (this one) exploring the music itself, and a (hopefully) shorter one talking about the recording and production. So, without further ado:

Picking the Piece

Maddalena—also Madalena or Magdalena, depending on whom you ask—Casulana was a fascinating woman of the Renaissance. As far as the Western canon is concerned, she is the first woman to have her music published (three volumes of madrigals, printed in 1568, 1570, and 1583 respectively). Plus, women of the era were generally only allowed to perform music as court musicians or as courtesans. Yet, Maddalena never remained at any specific court; additionally, her three books of madrigals were dedicated to three unrelated patrons. On top of that, we have no evidence that Maddalena worked as a courtesan. It seems Maddalena traveled far and wide, performing her own compositions and obtaining enough patronage to publish her own music.

Maddalena—also Madalena or Magdalena, depending on whom you ask—Casulana was a fascinating woman of the Renaissance. As far as the Western canon is concerned, she is the first woman to have her music published (three volumes of madrigals, printed in 1568, 1570, and 1583 respectively). Plus, women of the era were generally only allowed to perform music as court musicians or as courtesans. Yet, Maddalena never remained at any specific court; additionally, her three books of madrigals were dedicated to three unrelated patrons. On top of that, we have no evidence that Maddalena worked as a courtesan. It seems Maddalena traveled far and wide, performing her own compositions and obtaining enough patronage to publish her own music.

Despite the inspiring legacy, Maddalena remains mostly unknown. Few historical documents relating to her survive, and fewer people write about her. In fact, many of her madrigals have no recordings online, and “Ahi, possanza d’amor” (from her second book of madrigals) is one of them.

It’s no small task to interpret and record, let alone multitrack, a song for which you have no reference recordings. But, as an overzealous student of early music who loves underperformed repertoire, I felt I had to try.

My choice of “Ahi, possanza” was mostly made according to my limitations: I wanted a short piece that covered a range I could reasonably sing. “Ahi, possanza” was the first interesting-looking piece I found in the book (it’s the fourth madrigal) that fit the bill, so I went with it. And so, the massive task of interpretation began.

#1: Text and Translation

My first task after picking the piece was to translate the Italian text and interpret the music accordingly. Disclaimer: I have never taken a formal class in Italian, and I know that Italian poetry is a beast of its own with many double-meanings I can’t even begin to comprehend. So, all I could do was arm myself with my knowledge of Italian early music and a dictionary and hope for the best. This was what I came up with:

Ah, power of love, how at one time

You hand my heart both hope and fear!

For [love](1) I ask for death(2) and life

I burn and freeze, I am silent and cry aloud

for help as I perish; then I ask for death

Thus I serve others and happily wait [for death](3).

Overall, this poem is relatively straightforward. The first sentence is somewhat pensive, while the remaining lines become more action-oriented. The speaker concludes not with an explicit mention of “death,” (see the footnotes) but with “happiness.” Maddalena seems to find this proclamation important, because she iterates the final line twice. The only other line she repeats is the second: “You hand my heart both hope and fear!” So, she seems to focus on the emotions in the poem, rather than the “death.”

To respect these repetitions, I considered two options: sing the repeated content more tenderly, or more emphatically. For the second line, “You hand my heart both hope and fear!” I used both. In the Italian text, “speranz’e timor” (“hope and fear”) comes first, so I tried to convey those words more tenderly before growing into a more emphatic declamation of “al cor mi porgi” (“you hand my heart”). But for the final line, “Thus I serve others and happily wait,” I wanted to step away from any emphatic exclamation. Maddalena opens the madrigal delicately, with a sustained note in the top voice and little interruption from the lower voices. I wanted the madrigal to end in a similarly delicate manner, with a lighter articulation and lower dynamic level.

The other thing I did with my translation was search for text-painting, or musical gestures shaped according to text. Renaissance madrigals are notorious for text-painting, from staggered voice-entrances on words like “million” to soaring melodies on words like “climb.” I don’t think Maddalena put too much explicit text-painting into this particular madrigal, but I did respect the following words and phrases:

- “Ghiaccio” (“Ice”). I chose to add light vibrato to create a shivering effect.

- “Forte” (“Strong”). I emphasized the ‘F’ to create a strong onset.

- “Grido aita” (“Cry for help”). I emphasized the narrower vowels, particularly in the higher voices, to create a wailing sound.

I wouldn’t consider any of these choices to be ground-breaking, but I thought it was important to emphasize them. And so, with my interpretations on repetition and text-painting decided, it was time to tackle my next hurdle: speed.

#2: Tempo

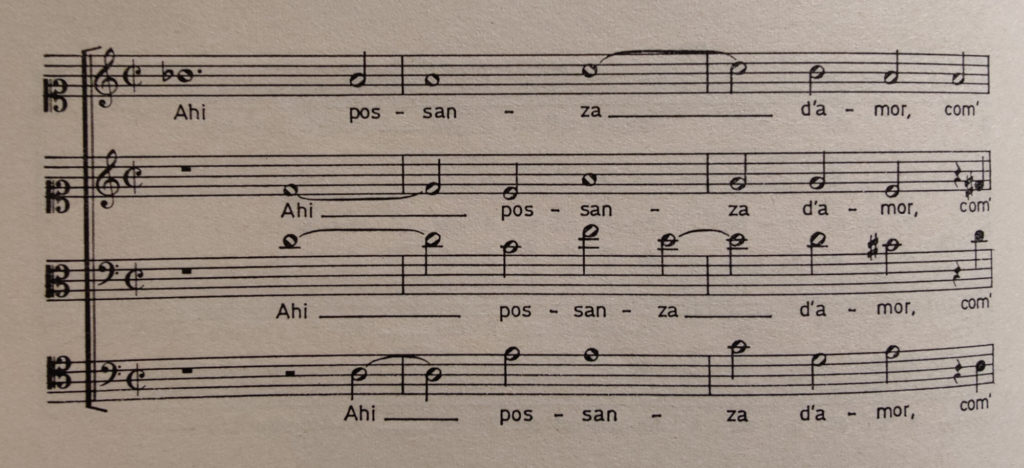

The Peabody Institute’s music library has only one edition of Maddalena’s second book of madrigals. It’s an older, Italian publication with horrible notation choices; my complaints about it are nearly never-ending. But as far as I can tell, it is the only official published version of the book, not counting the impossible-to-find manuscripts, so it was what I worked from. Here’s a picture of the first system:

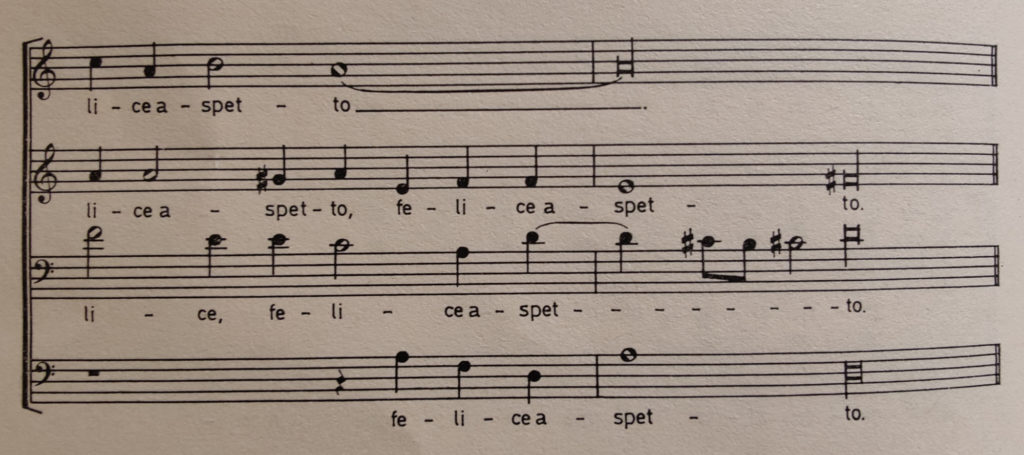

I’ve performed a lot of Renaissance music over the years, and in my experience, most pieces are felt best “in two.” This means that each bar above would be felt in two relatively slow beats: a completely reasonable tempo to take for the madrigal’s first few systems. On the other hand, the madrigal ends on this:

This passage is entirely possible to perform in a slow two. But with the constant quarter-notes, the eighth-note flourish, and the quick consonants batted from voice to voice, it would sound hectic at best.

Because of how I had interpreted the text, I didn’t want to madrigal to sound hectic. So, against my instinct to think of the madrigal in two, I decided to think of it in four instead. I didn’t make the madrigal twice as slow as I had thought of it before, but I did slow it down significantly.

This was a choice I flip-flopped on multiple times. Despite the quickness of the final section, much of the madrigal feels sustained, even static. The word “morte” (“death”) is always held for three beats, if not longer, which can become awkward when feeling the piece in four. Still, I decided to stay “in four” after much deliberation, and with that, it was finally time to consider pitch.

#3: Key Area

If you’ve listened to my recording while staring at the pictures of the score above, you may have thought, “Huh, the recording sounds oddly high.” That’s because I transposed the entire piece upward by a minor third. Maddalena writes a C3 as the lowest pitch, and I raised that to an E♭3.

I wish I could say I did this to respect historical pitch. We do have evidence that Venetian organs were tuned very high during Maddalena’s time—the A on the organ sounded significantly higher than the A we play on pianos today. But even though Maddalena was active in Venice, madrigals weren’t sung in churches with organs, and there’s just not enough evidence to make strong claims about performance pitch.

So why did I transpose everything upward? Simple: E♭3 is the lowest note I can sing, so I physically couldn’t sing it any lower. Depressing, I know.

On the flip side, why didn’t I transpose everything even higher? With the minor third transposition, the madrigal’s highest note becomes a G5, and I can sing a fair bit higher than that. Why go through the effort of keeping the piece at the very bottom of my range?

Part of this was due to the articulation choices I made. Remember, I decided to make the final part of the madrigal “delicate.” I didn’t want any notes in that section to be higher than an A♭, lest they come off as panicked squeaks or shrieks. Then I made my decision according to “key.”

I’ve put quotes around “key” because Renaissance madrigals aren’t in specific “keys.” (The explanation for this is too lengthy for this already-lengthy post.) Still, broadly speaking, this madrigal starts “in A.” By transposing it up a minor third, I moved the madrigal to “C.” If I transposed it up by a major third, I would have moved the madrigal to “C♯/D♭.” The thing is, most Renaissance music is composed in simpler keys, with fewer sharps or flats. (The explanation for this is also too lengthy for this already-lengthy post.) So, while C minor might be pushing boundaries with three flats, it’s at least better than C♯ minor, with four sharps. I wanted to avoid singing high A’s, so I couldn’t transpose any higher. Thus I resigned myself to the minor third transposition and moved to my final concern: ficta.

#4: Ficta

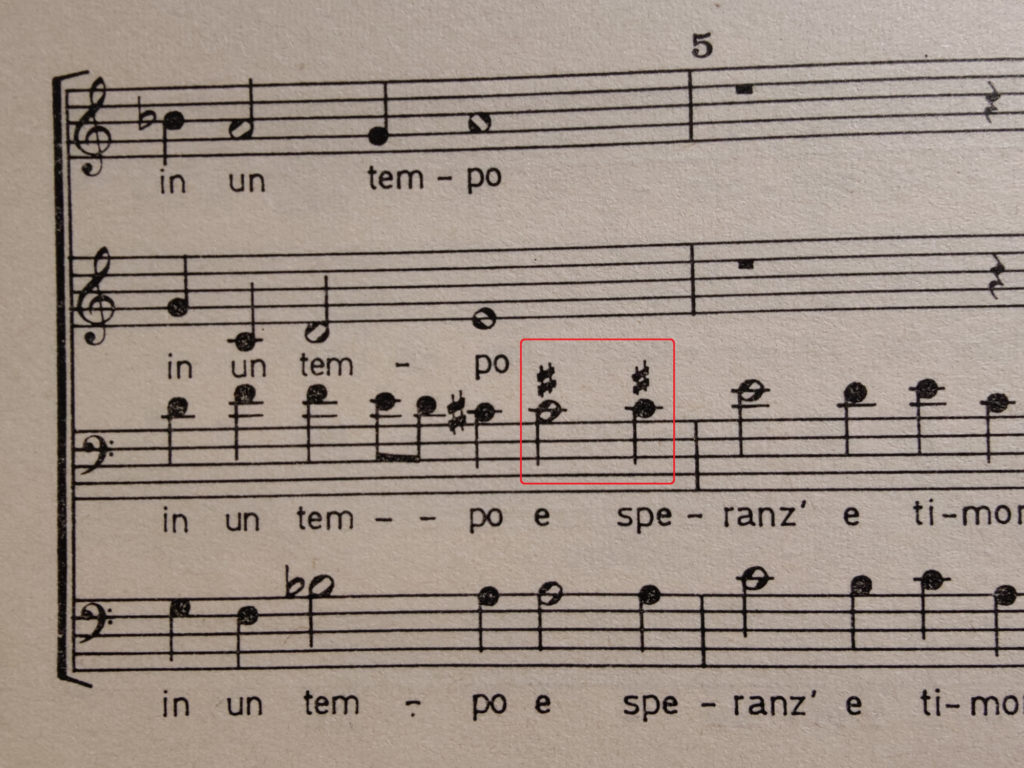

Musica ficta, or simply ficta, is the name for what we might call “adding accidentals.” In modern times, it refers to a performer or editor adding an accidental to a note because they deem it necessary. When a modern editor notates a ficta, they usually place it above the note head, rather than beside it. Actually, my horrible edition of this madrigal has a ficta right here:

However, I actually think this ficta is unwarranted. It might seem strange for the tenor to switch from a C♯ to a C♮ within a single measure, but I think it makes sense for three reasons:

- Going from “in un tempo” to “e speranz’e timor” is starting a new line of poetry, so you can easily argue for a resetting of accidentals.

- With the help of the upper two voices, the C♯ of “tempo” creates a Phrygian half-cadence, and since the tenor and bass start a new phrase with “e speranz’e,” they should likewise move away from the sound world of that half-cadence.

- Maddalena was notorious for making quick, chromatic color-changes, so a switch like this would be normal, perhaps even expected, for her.

There were three other ficta I decided to add to this piece. The first was relatively straightforward, and involved adding an F♯ like so:

Most Renaissance singers would add this one without batting an eye, I think. If you sang the G♯ to F♮ as written, you would create a melodic augmented second. Not only is the augmented second extremely rare in Renaissance music; it’s also saved for momentous occasions, and this throwaway eighth-note flourish is far from momentous.

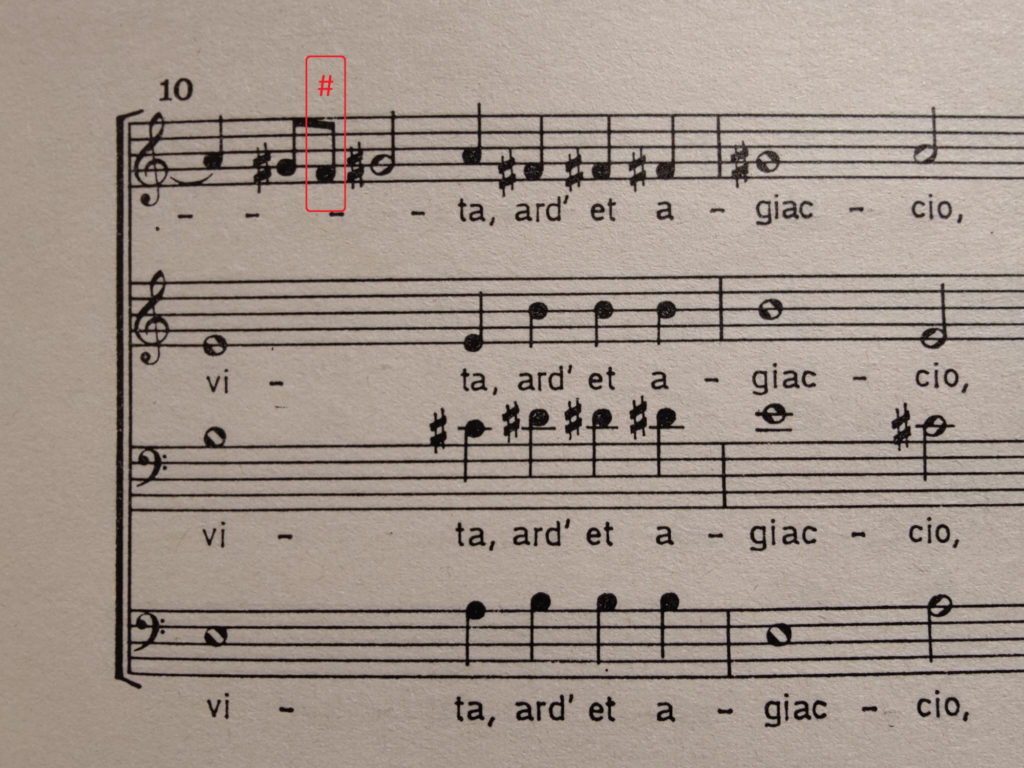

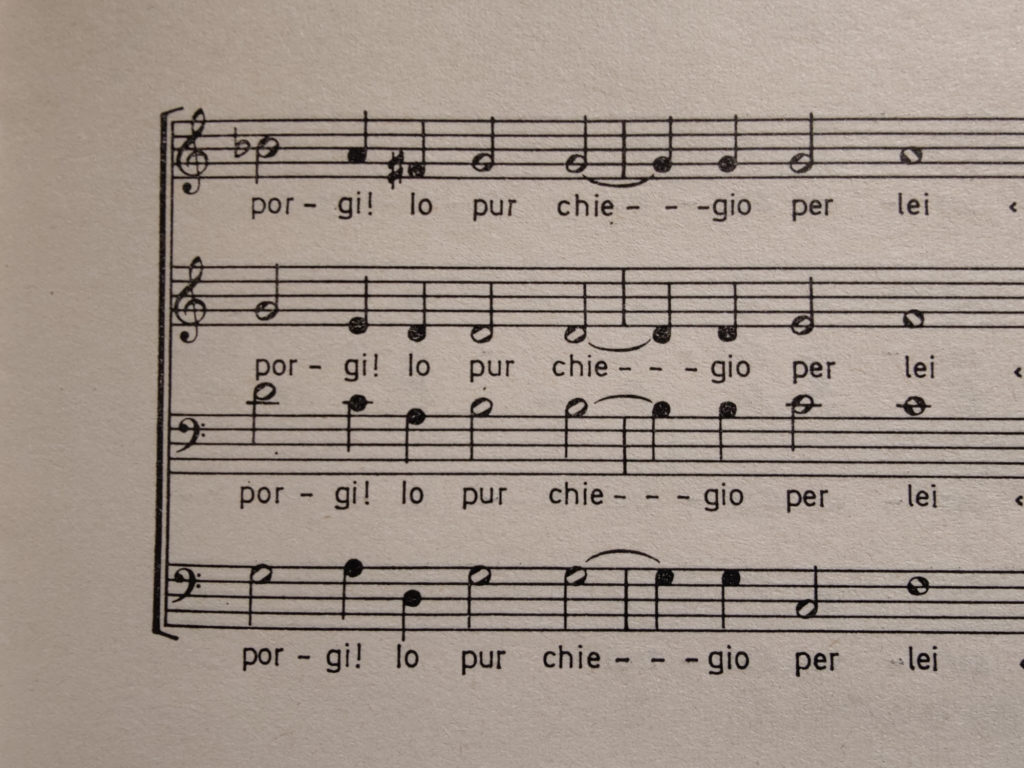

The final two ficta I added were for this rather odd section:

When singing through it, I knew something was off, but I couldn’t place the problem. At first, I thought it was just the tenor that needed fixing: I thought perhaps there needed to be a C♯ on the “porgi,” or a B♭ on “pur.” I decided to add the B♭ to “pur,” and I switched it back to B♮ on the next syllable to mirror the previous C♯ to C♮ gesture above. (Admittedly, I needed some convincing to do this, but I eventually decided that the text translation of “I ask” also warranted this color-change.) Still, I felt something felt off about the measure, and the C♯ on “porgi” did nothing.

Music theory is not my strong point, so I sought advice from teachers and friends on this one. In the end, we decided not to add a C♯ to the tenor, but instead to replace the alto’s D on “porgi” with an E♭. This changes the chord’s tonality from minor to diminished, which gives a little more tension; rightfully so, as “porgi” means “you give.”

~~~

Interpreting this piece, brief as it was, required long thought and consideration. Going into it, I didn’t think it would take nearly as long as it did. Nevertheless, it was a rewarding process and the completionist in me now wants to repeat it for as many of Maddalena’s madrigals as I can. We’ll see if that actually happens or not, given how busy I tend to make myself. But in the meantime, I hope this vomiting of words provided a slightly interesting read at least.

Footnotes

(1) This word is bracketed because the Italian simply says “her,” but I assume this is meant to be a double-entendre of Love being a cruel mistress.

(2) Although it didn’t strongly inform my musical decisions, it’s worth noting that madrigals are… risqué, to put it politely. If the word “death” appears in a madrigal, it’s usually referring to sexual intercourse. You can also assume that terms like “cold/ice” and “heat/fire” have double-meanings within madrigals; feel free to use your imagination.

(3) This phrase is bracketed because it doesn’t exist in the Italian, which ends on “happily wait,” but I assume it is the line’s unspoken finisher.

This Post Has 17 Comments

Pretty! This was an incredibly wonderful post. Many thanks for providing these details.

I’m so happy that the details I provided were interesting to you! Hopefully I am able to continue this series when I have the time to analyze and multitrack more madrigals. 🙂

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought

this post was good. I don’t know who you are but definitely you’re going to a famous blogger

if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

Wow, thank you so much! I am definitely not a famous blogger, but I appreciate the sentiment very much. 🙂

Bel post, l’ho condiviso con i miei amici.

Have you ever considered publishing an ebook or guest authoring on other blogs?

I have a blog based on the same topics you discuss and would love to have

you share some stories/information. I know my readers would appreciate your work.

If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to send me an e mail.

Awesome blog post.Really thank you! Really Great.

I want to to thank you for this excellent read!! I certainly loved every bit of it. I have got you bookmarked to look at new things you postÖ

As I site possessor I believe the content matter here is rattling magnificent , appreciate it for your hard work. You should keep it up forever! Good Luck.

Bel article, je l’ai partagé avec mes amis.

Hi there! This post couldn’t be written any better! Reading through this post reminds me of my previous room mate! He always kept talking about this. I will forward this article to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

I don’t usually comment but I gotta state regards for the post on this amazing one : D.

You really make it seem so easy with your presentation but I find this matter to be actually something which I think I would never understand. It seems too complex and extremely broad for me. I am looking forward for your next post, I will try to get the hang of it!

Hey I am so grateful I found your blog page, I really found you

by mistake, while I was researching on Aol for something

else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a

fantastic post and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have

time to read through it all at the moment but I have

book-marked it and also added in your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read

a great deal more, Please do keep up the superb jo.

Hey there, You’ve done an incredible job. I?ll definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends. I’m sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.

I?m impressed, I have to say. Really rarely do I encounter a blog that?s each educative and entertaining, and let me tell you, you have got hit the nail on the head. Your idea is outstanding; the difficulty is one thing that not enough persons are speaking intelligently about. I am very blissful that I stumbled throughout this in my seek for something relating to this.

I enjoy you because of your whole effort on this blog. My niece really loves managing research and it is simple to grasp why. Most of us notice all relating to the dynamic method you render insightful solutions via your web blog and increase response from the others on that subject while my girl is certainly understanding a great deal. Take pleasure in the remaining portion of the year. You’re the one performing a terrific job.